All illustrations by Brigid Deacon.

Lessons From Psychosis

Ari Potter

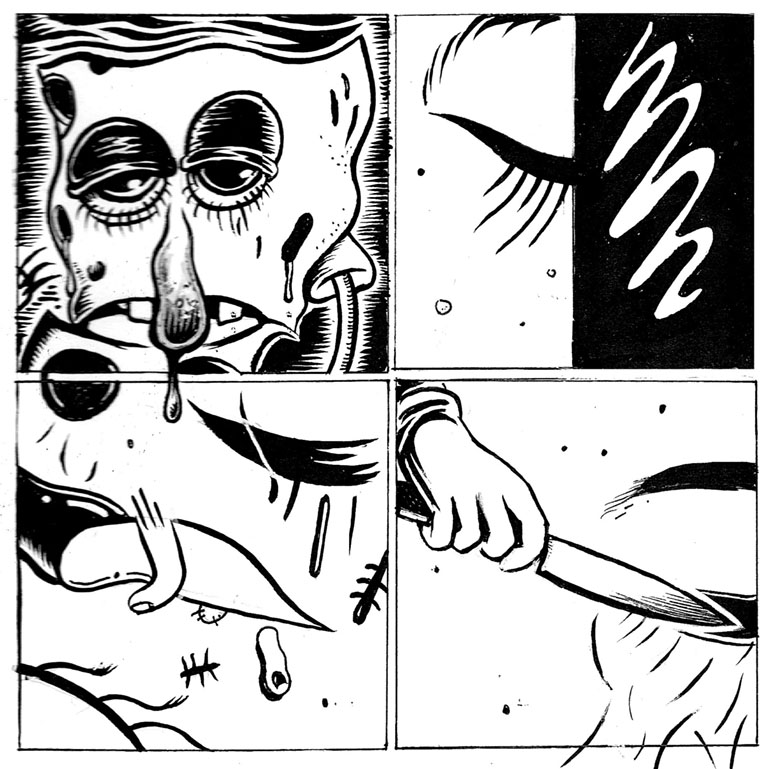

I’m dead.

I died of a heroin overdose. I’m dead.

It’s all going to be OK.

Everyone I know is dead too.

But they’re not. That’s the big secret – they’re immortal.

They’ve been waiting for me. I died of a heroin overdose.

This is what I insisted to the paramedics over and over again. I found their incredulity amusing, maniacally so. You’ll realise one day. Think of ants walking along a tape measure, a spiral in a spiral in a spiral, and you’re at the very end of it, and you have to one by one wait for everyone else to come to the same realisation as you, like dominoes falling one by one. You’ll realise soon. You’re such a beta male. We’re all dead: I died of a heroin overdose. What did you die of? No imagination?

I thought we were in hell, or purgatory. I don’t have enough knowledge of Dante’s circles to have thought through the specifics of where I was trapped, but I knew it was forever. I thought the children waiting in the corridor were angels. I now know that it was Homerton Hospital, or the Royal London, maybe. I forget. I remember that they were dead too, I thought they’d died young. I thought we were all waiting for the paramedics and then the doctors to realise. We were all dead. I died of a heroin overdose.

‘Come and get me. I’m in hospital. Just trust me, it’s going to be so beautiful. I’ll pay for the Uber.’ It didn’t matter that they’d taken my phone and wouldn’t let me speak to anyone. I spoke to one of the angels, or the parents of one of the angels, sat in the starkly lit waiting area. Let me use your phone, I just need to go on Facebook, just to send one message. It was my one phone call from jail. I was determined to escape and I just needed someone to save me where my friends wouldn’t. ‘You’ve got to come and help me, they’re keeping me here, they’re keeping me from you.’

I was afraid. ‘Is it time now?’ I asked, wide eyed, swallowing tears. It’s time to go upstairs. I curled up and put my arms around Rupert’s neck. I’m going to die now. It will be OK, won’t it? I swallow and take in the heat of his face, his cheeks, his familiarity. It’s time to go upstairs. It’s going to be OK, isn’t it, Rupert? You’ll be here with me. I’m dying but you’re going to be here. We’ll be like this forever now, my golden emu. It’s time to go upstairs now.

How do I get out of here? How do I get out? I kept taking off my gown, these bizarre white apparitions covered in green diamonds. I felt like a ghost, or maybe I was just playing, I don’t know. I’m pregnant, you’ve got to let me out. You’re not pregnant, you’re bleeding. I can prove it. My breasts are exposed. An orderly had taken off my gown and my breasts were on show. I’m proving you’re not pregnant. Or maybe it was me who took it off, who knows. I don’t remember. They didn’t believe I was pregnant. I couldn’t escape. I threw my pink flip-flops out of the narrow sliver of window, as if I could teleport to join them.

Baba, baba, please just listen to me.My mother is speaking Bengali. She’s in the bathroom with me. I don’t know what she’s doing but she’s imploring me to listen to her. I’m wet. The water is cold, she’s washing me. I am a child being bathed. I don’t know where my clothes are. I’m wearing what feels like a nappy. I’m bleeding. I need my medicine. I need my vitamin D and my femodene and my sertraline. That’s what made you ill, says my father. I don’t understand. Why won’t you give me my medicine? If you just give me my medicine I’ll be OK.

My mother and I are sat in a room. We’re playing on an iPad. I’m making her do a quiz. I just want her to finish the quiz. A woman who I think is related to me, she’s Bengali but dresses English and wears a nose ring and has very stylised hair, somehow she has the answer but I can’t work out where she fits. I think she might be related to me.

Georgina, you’ve got to let me out. Please, please, I love you. You have to let me out. Please. I’ll never keep anything from you again. Please, you’ve got to let me out. Please. Please let me out. Or give me some paper, at least. I need more than one sheet. This isn’t enough. Please, you’ve got to give me some paper. I need my mum. Why won’t you let me be near my mother? She’s in the other room. She’s not a doctor, she’s my mum. My mother is a doctor too.

Were you really talking about tantric sex? I looked it up. I couldn’t believe you were talking about it. I look up, coyly. Yeah, I was. We are alone in my room. The lights are dimmed, it is atmospheric. There are shrieks from somewhere else on the ward. Hold on, I need to go and see what that’s about. I’ll be back. It is late, past midnight. The lights in my room have been dimmed and could pass for mood lighting. He is so stupid. He stays in my room, talking to me until late into the night. He wraps me in a blanket. We are alone. He has broken some rules, I think he knows. But he stays, and we talk. I introduce him to Cathy and Georgina when they next visit. They’re amused. They raise their eyebrows: nice to see that you’ve made some friends. He keeps coming to my room and asking me questions but soon I pretend to be able to read and he watches as I fall asleep. When I am out, I go to the GUM clinic and get a pregnancy test.

***

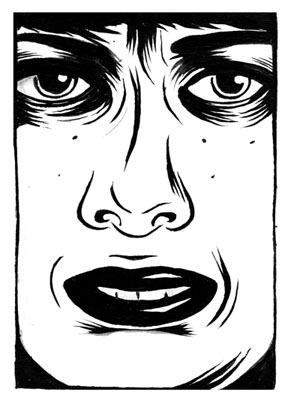

'You’re in Mile End Hospital. You’re safe. They’re treating you. You’re not well.’ This was the gist of messages from friends that I managed to contact using the on-ward iPad that helped me to emerge from my missing month. Initially, I was confused, as I pieced together the puzzle of my confinement. Where I was, why I had ended up there, how long I had been a prisoner. Slowly, as the reality that most of us share returned to me, I felt like I had ruined my life.

In the weeks and months that followed, this feeling intensified as I found myself unable to simply pick up where I’d left off. I was unemployed, vulnerable, and hopelessly embarrassed. I tried a raft of different anti-psychotic medicines, hoops I had to jump through in an effort to convince a team of mental health professionals that I didn’t need to be medicated to stay in the world. Writing this now, six months later, I still feel an acute sense of nauseous shame to think of it. Regaining my position pre-psychosis has taken time, and effort, and I’m shy of where I was before it: I will never get back that September, all those Almodovar tickets I bought, that spa trip, that birthday. This experience can never be undone.

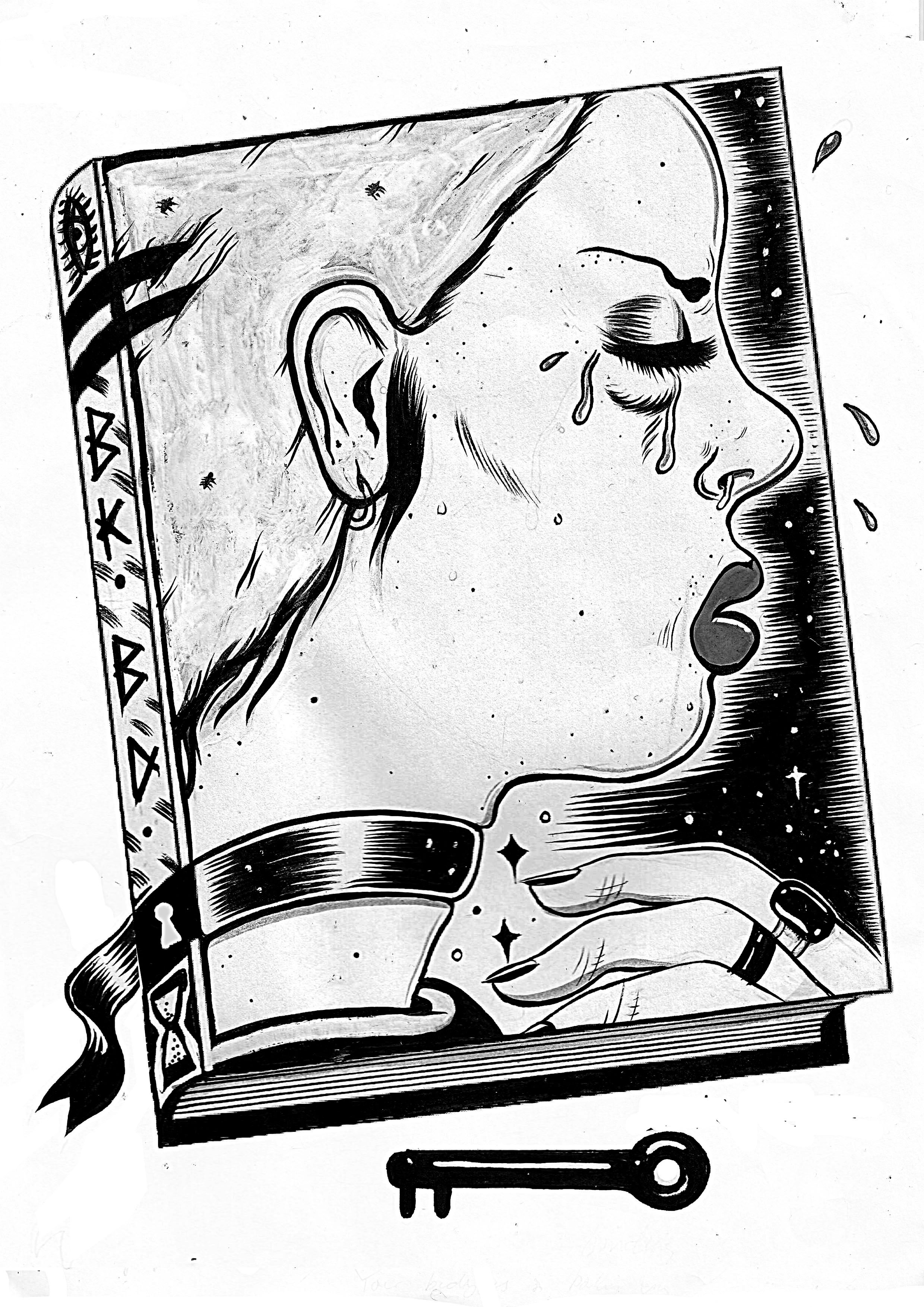

There is one positive to be gleaned from the ordeal: it's undeniably given me something to write about. Of course, there's the experience of being a mental health inpatient, what it's like to have amnesia of a significant period of your life, what it's like to have something big and terrible and unusual occur in an otherwise unremarkable existence. People are curious and I'm at peace (just) with the fact that I'm now the friend of a friend who had a bad trip, the anecdote worthy of a Guardian experience. But that's not what I mean: my delusions themselves are the really juicy topics.

Imagine you are completely immersed in a parallel world. Everything looks the same; you have all of the same memories and characters making up the fabric of your life. However, you have a fundamentally different understanding of it all. It is like all of a sudden believing that God exists, or more aptly, like the laws of physics no longer apply to you. You're Harry Potter when you find out he's a wizard. (Incidentally, several concepts from Hogwarts cropped up in my psychoses so JK Rowling can feel contented that her world is firmly knitted into the depths of my consciousness.) I don't have to invent a new conceit or idea; the hard work has been done for me. I can be lazy and simply recall and describe. 'A writer's gift', it's been called.

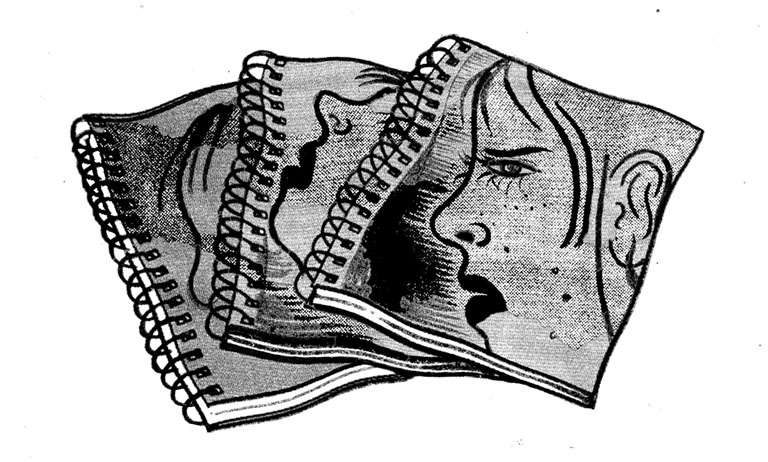

Challenges remain: I'm motivated to write it all down partly to try to “make something” of an overwhelmingly negative time. To cast my mind back to the relevant memories, I have to first wade through the shame and despondency of the real world consequences that go along with entering a reality you invented. 'You didn't ruin your life, it was just a setback.' Getting to the point of committing useful words to paper involves spending disproportionately more time dwelling and ultimately processing.

I’ve interrogated where the feeling of shame comes from. In part, it’s the vulnerability and openness that I displayed during psychosis, which feels a bit like being drunk in a group of sober people. Then, there's the difficulty of describing my delusions in a way that makes sense to anyone but me. A delusion is not a thought experiment that you can invent in someone's mind by asking them to imagine a set of circumstances. It's a whole narrative and set of truths that you need to recreate with all their layers but without boring the reader. 'It all makes so much sense right now', I kept saying at the time. To others, it doesn't, or at least not as easily and immediately.

Once the problem of faithfully describing has been surmounted, the question of if it's interesting to others remains. It's tricky for me, or anyone who knows me, to assess subjectively. It gets blurred with the novelty that a weird thing happened to me and I can remember it. Sometimes, when verbally recollecting a memory, I get the sense that people are fascinated at being in the presence of madness. I have to access that place of derangement that is curious for spectators. It's temporary and contained so ultimately it's safe. But is the content itself of potential value?

It's revealing, that much is certain. My brain churned them out and anyone with a rough knowledge of my history and upbringing can see the threads running through them, the connecting points to my real life reality. It makes me vulnerable, ripe for pop-psychoanalysis. It's embarrassing to me that the rabbit holes of my mind are so obvious. Abandonment, acceptance, control. The themes of my insecurities are so plain in my delusions that I cringe.

In part, it's an act of remembrance. An almost religious gesture to what brought me back to Earth. The last few days of my sojourn were obsessed with writing. I was convinced I had to write it all down, everything, and then I would be able to escape. In particular, I was convinced I had to send a publisher friend a copy of the manuscript I had been writing (I squirm as I type this) as the final mission. Of course, I know that isn't what happened. Yet a superstitious part of me wants to respect the promise, just in case. If nothing else, I guess it proves my subconscious really wants to be a writer.