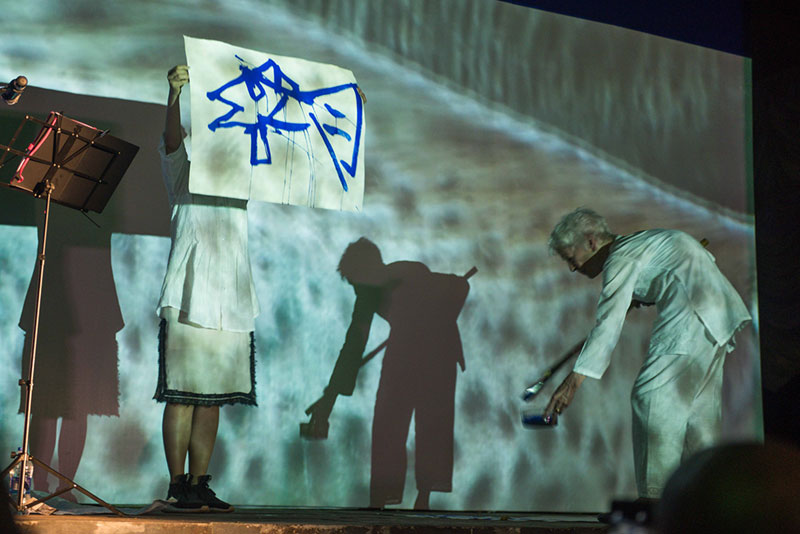

Himali Singh Soin, Radar Level, performance still, Frozen World of the Familiar Stranger, Delhi, India, 2016, photo: Khoj Studios

Joan Jonas, Ocean–sketches and notes, The Current Convening #2, Kochi, Kerala, India, 2016, photo: TBA 21 Academy

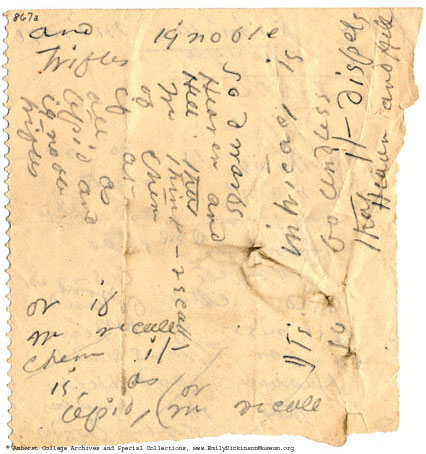

Emily Dickinson, Envelope Poems, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

My Joan Jonas

Himali Singh Soin

On Emily Dickinson, Susan Howe, Joan Jonas, and Mary Ruefle.

Recently, while parsing Emily Dickinson’s envelope poems—poems scrawled along the folds, around the seals and inside the flaps of envelopes—I began thinking about transmission: compressed fragments of time both immediate and unrecoverable. They were some of irony’s most visual productions: a private life made external and handed over to the postal service.

This is a collective gathering of intimacy. This is an epistle to you, my reader.

In the preface to the collection of envelope poems, the poet Susan Howe writes, “to arrive as if by telepathic electricity and connect without connectives.”

To make false intersections. To cross-fertilise divergent fields of inquiry. To offend formalism’s imperial goals. To undermine the hierarchies of knowledge and amalgamate temporalities. To voice poetic dissent. That is to say, to fold linear time. To announce a multitudinous cacophony of voices, to diverge from the clock’s capitalist, colonial tick, to dance to a polyphonic rhythm. To make a music of togetherness around which we gather.

Joan Jonas: I always thought the activity of putting one object next to another was like making a visual poem.

I was at a performance, Oceans–sketches and note, 2016, by Joan Jonas in the Vasco de Gama square of Kochi in southern India. A video of the submerged world—jellyfish, octopi, urchins and a slew of curious creatures of the oceans—was projected in the background, while the artist, layered in crushed translucent paper and fabrics, moved across the stage chronicling tales from the deep sea, painting, gesturing, ringing bells. She was an alchemist of opacities and dimensions, much like Time itself. Her practice purposefully overlays strange temporalities, at once set in the ethereal and the embodied, in archival footage and in live drawing, in mark-making and meteoric flashes.

Susan Howe to Joan Jonas: I am a poet and you are a performance and visual artist. It’s sometimes difficult to relate the two things, but I notice in review after review, your work is referred to as poetic or poetry.

Joan Jonas: I was very influenced by the idea of poetic structure – the way a poem is put together in relation to the way I put an image together.

Joan Jonas and Susan Howe’s friendship goes back to when they were at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts together. Joan Jonas’s The Juniper Tree (1976) was inspired by Howe’s son’s favourite fairy tale. He may or may not have been conceived in Jonas’s New York apartment, after a late night of live art and roving conversation. Jonas and Howe’s effects on one another are direct and digressive.

Jonas possesses language, and often dislocates herself by telling stories that jumble time. She uses the tropes of poetry—metre, metaphor, mistake—which are, arguably, a mortal form of time travel.

Joan Jonas to Jamie Stevens: I only work with time in that I deal with it as a material that I

manipulate, and divide and rearrange.

Jonas’s references are unbound—an academic’s nightmare—and myriad. She borrows from poets, philosophers, and scientists alike. The varied registers of her stories, drawings, and sculptural props find no reason for reconciliation: woven through, collaged, collated, edited, torn, and dissolved with the multiplicity of a singular consciousness at work.

Joan Jonas: A poem is like a condensed image.

A poem is a totemic object. A mask.

Susan Howe in My Emily Dickinson (1985): A poem is an invocation, rebellious return to the blessedness of beginning again, wandering free in pure process of forgetting and finding.

Howe’s book, My Emily Dickinson, is a poeticritical analysis of Emily Dickinson’s poems, interspersed with historical vignettes, literary quotations, autobiographical anecdotes, and her own philosophical meanderings. It makes for an asynchronous text, penduluming backwards and forwards in time, and in doing so, holding up a mirror to the present moment and its barrage of media.

This free process of forgetting and finding made me think of Mary Ruefle’s own claim to Dickinson, in her book of essays, Madness, Rack and Honey: Collected Lectures (2012), in a chapter called ‘My Emily Dickinson’—an italicized nod to Howe—in which she loosely links Emily Dickinson to Emily Bronte across ages.

Mary Ruefle: A child’s block with the letter E on it.

There is something I can’t explain. Connections borne from intuition.

Susan Howe: I have always been interested in folktales, magic, lost languages, riddles, coincidence, and missed connections.

Mary Ruefle: I don’t know if there is a connection … Sometimes we know there is a connection. Sometimes we wonder if there is a connection. And sometimes we know there is no connection, but we wonder then if one might be possible.

The four voices bump into and ring with(in) each other like folkloric artefacts in an abandoned house. The act of finding webs, patterns and missed connections is an act of interpretation. This adds another layer of temporality: to read into and out of and in between these tangential lines.

Susan Howe on Emily Dickinson: Pulling pieces of geometry, geology, alchemy, philosophy, politics, biography, biology, mythology, and philology from alien territory, a ‘sheltered’ woman audaciously invented a new grammar grounded in humiliation and hesitation.

Susan Howe performs telepathic alchemies between her contemporaneity and the echoes of the Emily from the past. In doing this, she radicalises feminine language, the idea of the we.

Emily LaBarge on Susan Howe: Howe convinces us that intuited connections are real and possess a logic of their own, and that supposed breaks in continuity, in history or associations or sentences, are often the very place we should look to forge new connections.

I wonder now (if you are still with me), if there are any synaptic signals transferring in this brief encounter, or if you are drawing blanks. While the four poets actively use the noisy imagery of lists and pullulating things, they also rely on narratives—solidarities—that dance their own dissent in the spaces between things, in the margins around pages, the edges of images and the auras of things.

Joan Jonas: Better to be silent. That is what the glacier does.

Jonas devises ecological trajectories between the permanence of a human imprint on Earth, and the impermanence of the medium chalk and stage. She draws and erases, draws and erases.

Mary Ruefle, quoting Fernando Pessoa in her essay on ‘Erasures’: Everything stated or expressed by man is a note in the margin of a completely erased text.

Dickinson’s poems are scratched through, deleted, wounded and healed over, palimpsestic.

From Emily Dickinson’s ‘Envelope Poems’: Long years apart can make no / Breach a second cannot fill -

Maybe using erasures is a way of materialising absences, of healing from loss. A way of making time circular, so that it ends where it begins where it ends.

Mary Ruefle: I use white-out, buff-out, blue-out, paper, ink, pencil, gouache, carbon, and marker; sometimes I press postage stamps onto the page and pull them off–that literally takes the text right off the page! Once, while working on an all-white erasure, I had the sense I was somehow blinding the words—blindfolding the ones I whited-out, and those that were left had to become, I don't know, extra-sensory or something. Then I thought, no, I am bandaging the words, and the ones left were those that seeped out.

Joan Jonas: Just thinking about the biosphere, or Native Americans and their land, you have to wonder about the significance of your own work. It could all disappear, just like that.

It felt like I dove deep into the ocean with Joan Jonas, travelled in dark, empty space with her through galaxies and aeons. And then obliterated. She did not fear getting lost, I was scrambling. Jonas’ performances, particularly when she appears in masks and accoutrements from indigenous cultures, have a deeply childlike and folkloric quality, qualities that can often make them appear de-historicized and uncomfortably appropriated. In the duration of the performance, however, they render you hybrid. Transtemporal. They invite you to lose yourself, to disappear, and then emerge queered, forge new correspondences always with an ear to the origin.

I am reminded ofremember again that thing Howe wrote.

Susan Howe: To arrive as if by telepathic electricity and connect without connectives.

The experience—though in the most public of places—was my own. Still, if you are reading, my mediation has been slipped in an unsealed envelope. The friendship between the four poets—real and imagined—and between the poets’ and myself, and now between you and me, is a vibrant site of insistence and resistance. This is my telepathic missive to you. A published intimacy.

Susan Howe: What is the communal vision of poetry if you are curved, odd, indefinite, irregular, feminine. I go in disguise. Soul under stress, thread of connection broken, fusion of love and

knowledge broken, visionary energy lost, Dickinson means this to be an ugly verse.

My Joan Jonas is concrete, embodied, disembodied, winged and witched, and dispatched in a spirit of friendship. It is a fusion of love and knowledge. Here, the rules of language can be dismissed. We know that unactivated ideas are like blank spaces, and that theory must be practiced, art must be transmitted. These broken links allow us to think socially, to believe in language’s critical possibilities, and in the we that makes.

Himali Singh Soin is a writer and artist based between London and Delhi. She is currently working on a book from the polar circles called we are opposite like that.